By SUSAN DOMINUS

Published: May 8, 2005 � 2005, New York Times

“After tomorrow, I’ll have done everything there is to do,” Jason Hatch said one night in February, staring wistfully into a near-finished glass of beer at a bar in Shrewsbury, England.

“After tomorrow, I’ll have done everything there is to do,” Jason Hatch said one night in February, staring wistfully into a near-finished glass of beer at a bar in Shrewsbury, England.

Just a few hours earlier, he and some friends were enjoying a raucous, boisterous evening, all but driving out the other diners at a decorous French restaurant. Now, after several drinks at the bar, the lateness of the hour and the increasing proximity of Hatch’s plans for the next day seemed to be catching up with him, and his mood took a turn toward the tense. By the following afternoon, Hatch, a 33-year-old former house painter and contractor, intended to scale a government office building near the prime minister’s residence at 10 Downing Street. His friends, many of them co-conspirators, had gone home, the revelry had died down and he was clearly trying to regain some focus. Was he getting nervous? ”The police say Jason doesn’t have fear like other people,” he said, speaking of himself in the third person, perhaps hoping they were right.

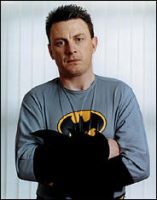

If, earlier in the evening, others at the restaurant looked over to Hatch’s table (and given the noise emanating from it, they surely did), they would have seen that Hatch wore a T-shirt emblazoned with the purple logo ofFathers 4 Justice, a political group that is well known in Britain for staging high-profile stunts to raise awareness about the custody rights of divorced and separated fathers. (In one memorable incident, a member pelted Prime Minister Tony Blair with a condom filled with purple flour.) Some might even have recognized Hatch and made a note to mention their brush with semi-celebrity to their friends: this was the man who scaled Buckingham Palace last year dressed as Batman, unfurling a banner in support of fathers’ rights and spending more than five hours perched on a ledge near the palace balcony as security officers tried to talk him down. The event, which made news around the world, saturated the British media for nearly two days.

Hatch was arrested, but he was promptly released and never charged with a crime. ”I even got me ladder back,” he likes to mention. Nonetheless, the police keep a close eye on him, even outside his own country. Several months after his Buckingham Palace stunt, Hatch, hoping to broaden his group’s support in the United States, flew to New York, where a team of police tailed him and his colleagues for the duration of the five-day visit. (The cops finally announced themselves, befriended Hatch and his fellow would-be protesters and ended up escorting them to various downtown nightclubs, passing them off as royalty — anything, apparently, to keep them from putting on capes and scaling the Brooklyn Bridge.)

At the bar in Shrewsbury, as Hatch fretted about the details of his next major stunt — could he get a lighter ladder by tomorrow? — he seemed overtaken by melancholy. He hadn’t been sleeping, he said; his head ached. Three and a half years ago, Hatch’s second wife left him, taking their two children with her. When he finally caught up with them, a family court granted him visitation rights. He later claimed in court that his wife regularly ignored the ruling, refusing to let him see the kids, but, he told me, the court did little to satisfy him. ”It really takes it out of me,” he said. It had been so long since he’d seen his kids — Charlie, who’s 5, and Olivia, who is a year younger — that their mother now claims they didn’t want to see him, he said. They had started calling their grandfather Dad. (His wife has declined to speak to the press, other than to say that Hatch’s activism has disturbed the children.)

Hatch first contacted Fathers 4 Justice a year and a half ago, after reading about their protests in the newspaper. The group’s founder, Matt O’Connor, a 38-year-old divorced dad with a gift for public relations, visited Hatch at his home in Cheltenham to gauge his commitment — and, as it turned out, to scope out some possible locations for protests. Two weeks later, Hatch found himself with three other fathers, standing atop a 250-foot-high suspension bridge in Bristol, dressed like a superhero, hanging a Fathers 4 Justice banner. For the 28 hours that Hatch and his colleagues remained on the bridge, the police rerouted commuters, as reporters and curious pedestrians gathered below. After years of ineffectual legal struggle, Hatch could finally see results: traffic had literally stopped on account of his cause. He went on to scale a series of other targets, including several court buildings, York Minster Cathedral and, finally, Buckingham Palace. The grandiose, symbolic gesture had become more satisfying than the niggling, humiliating legal maneuverings that never seemed to pan out.

Hatch’s sense of despair about his estrangement from Charlie and Olivia has apparently swept away any concern he might have had about the most basic requirement of parenthood: his continuing good health. When he scaled the ladder at Buckingham Palace, the guards cocked their rifles, a sound captured chillingly on a videotape of the event. ”I’m not afraid to die, but I don’t want to,” Hatch, who now has a 14-month-old daughter with his current girlfriend, Gemma Polson, told me. ”I feel sorry for Amelia, obviously — Amelia being me little daughter. If anything happens, she’s going to lose out, but I still have to do it. I still have to go out there and get the law changed, and when the law’s changed, you won’t see me again.”

Now a full-time salaried havoc-wreaker for Fathers 4 Justice (the group raises money through membership fees), Hatch has a martyr’s self-righteousness but also an adman’s instinct to feed the media beast ever bigger morsels of a story. ”If I got shot, but survived,” he said just before heading to bed for the night, ”that would be brilliant.”

Although some of the issues raised by Fathers 4 Justice concern quirks of the British custody system, most of them overlap with demands of divorced-fathers’ groups in other countries: stronger enforcement of visitation rights, more shared-custody arrangements, a better public and legal acknowledgment of a father’s importance in his child’s life. In the United States, the influence and visibility of those groups have waxed and waned since the mid-70’s, but they appear to be agitating now as never before. In the past year, class-action suits have been filed in more than 40 states, claiming that a father’s constitutional right to be a parent guarantees him nothing less than 50 percent of the time with his children. And on the legislative front, last spring Iowa passed some of the strongest legislation to date in favor of joint physical custody — the division of the child’s time between the two parents as close to equal as possible. The policy, which resembles some legislation that Maine passed in 2001, encourages judges to grant joint physical custody if one parent requests it, unless the judge can give specifics to justify why that arrangement is not in the best interest of the child.

There are dozens of fathers’ rights groups in the States, including the American Coalition for Fathers and Children, Dads Against Discrimination and the Alliance for Noncustodial Parents Rights. They may not have the name recognition that Fathers 4 Justice has on its own turf, but they work quietly behind the scenes, pushing for custody laws like the ones Iowa and Maine have passed, lobbying Congress and generally doing what they can to improve not just the rights but also the image of divorced fathers. In this last task, oddly enough, these groups have benefited from federal initiatives designed to motivate divorced or never-wed fathers who care all too little about their kids, as publicly financed ad campaigns remind the public how indispensible fathers are. (”Fathers Matter,” shouted ads on New York City buses last year.)

Fathers’ groups also benefit from a more general recognition that fathers, at least in some socioeconomic circles, are now much more involved in their children’s lives. Some of that involvement is born of necessity, given how many mothers work, but necessity also seems to have effected a cultural shift, ushering in the era of the newly devoted dad. The traditional custody arrangement, with Mom as sole custodian and Dad demoted to weekend visitor, may have been painful, but practical, in a family with a 50’s-style division of labor; but to the father who knows every Wiggle by name, the pediatrician’s number by heart and how to make a bump-free ponytail, such an arrangement could be perceived as an outrage, regardless of what might be more convenient or who is the primary caretaker.

On the other hand, divorced dads still face some serious image problems, a function of well-known statistics that are hard to spin. In the United States, in the period following divorce, one study has found, close to half of all children lose contact with their fathers, with that figure rising to more than two-thirds after 10 years. Although child-support payments have crept up in recent years, in 2001 only 52 percent of divorced mothers received their full child-support payments; among women who had children out of wedlock, the number was around 32 percent. Fathers’ rights groups have a tall order explaining those statistics, convincing judges — and the country at large — that if fathers skip town, or refuse payment, it’s a function of how unfairly family courts treat them rather than the very reason that the courts treat fathers the way they do. Kim Gandy, president of the National Organization for Women, told me that fathers’ rights groups are ”focused only on the rights of fathers, and not on the rights of children, and particularly, not on the obligations of fathers that should go with those rights.”

Some fathers’ rights advocates in the United States fear that the Fathers 4 Justice approach to image overhaul will slow the movement’s bid for respectability, but others are ready to try some kind of major action. To date, none of the fathers’ groups in the States have managed to spark a sympathetic national dialogue in the way Fathers 4 Justice has done in England — striving to recast divorced dads, en masse, as needy and lovable rather than as distant and neglectful. Without that sea change, fathers’ groups here in America acknowledge, there’s only so far they can go in changing the way judges rule, no matter what the laws can be made to say.

In January, Ned Holstein, president of Fathers and Families, a Massachusetts organization committed to improving fathers’ access to their children, decided to devote one of the group’s bimonthly meetings to a debate about the merits of Fathers 4 Justice-style tactics. To date,Holstein’s organization has pursued its goals through traditional nonprofit pathways: hiring a lobbyist, an intern, a program coordinator, all financed by member-donated dollars. The group reached a milestone last fall, when it managed to put a nonbinding question about shared custody on the ballot for the November elections; 86 percent of those who voted on the issue supported a presumption of joint physical and legal custody. Despite the results his approach has yielded so far, Holstein told me before the Fathers and Families meeting, he was curious to see how his constituency would respond to the idea of following Fathers 4 Justice’s lead, opting for what he calls ”the flamboyant route.”

Holstein, now 61, resolved his own divorce amicably about 10 years ago, arranging for shared physical custody of his kids. But the court consistently treated him, he says, like a crank, and he started to collect stories from fathers who fared far worse. Before long he had a cause. A doctor who frequently testifies in trials, Holstein has an easy way with statistics and studies and evidently enjoys his public role. As he drove me to the group’s meeting at a private school in Braintree, Mass., he made an eloquent case for increasing fathers’ access to their kids. He has no problem with the existing ”best interests of the child” guideline that judges follow in reaching custody decisions, he explained. He simply contends that, as a matter of practice, judges underestimate how important a father’s active involvement is to the best interest of the child — and weekend visits twice a month don’t constitute active involvement, in his view. ”At that point,” Holstein said, ”visitations become painful, because they remind parent and child of what they don’t have, which is intimacy.”

Holstein arrived at the school to find 40 or 50 men and a handful of women (mostly girlfriends and second wives) already there — a fairly typical turnout, he said. After a short, rousing speech to start, Holstein turned the subject of the meeting to Fathers 4 Justice. Matt O’Connor, the British group’s founder, had declared purple the color of the international father’s movement, and Holstein said he was hoping the men in the audience would consider wearing a purple ribbon. ”I hope you will join me, and won’t decide it’s too . . . whatever,” he said with a nervous laugh. ”Now I need someone to go around with the scissors, so we can cut up and pass around some ribbons.”

This apparently sounded suspiciously like sewing; there was an awkward silence. Finally, a woman in the third row raised her hand, but Holstein balked. ”We can’t let a woman do this!” he said.

”She wants it done right!” someone chimed in, getting a big laugh. Soon enough, a middle-aged man in a mock turtleneck and khakis rose to the challenge, and the ribbons started circulating.

Choosing purple was one of Fathers 4 Justice’s more savvy branding decisions. The color works for the group for the same reason Holstein worried his fathers might feel too ”whatever” wearing it — it’s sort of a silly color, a kid’s color and definitely not macho. Given the particular American constructs of masculinity, it’s not clear how other elements of the Fathers 4 Justice aesthetic would play in the States: could a man running around in public in tights and a cape, mocking the law and defying security, ever be an emissary on behalf of American fatherhood? For some time now, O’Connor has considered starting a march of fathers in drag (”It’s a drag being a dad,” the signs would read), which suggests the size of the gap between his sensibility and that of the average American.

Humor has clearly been a key to the success of the British campaign, distancing Fathers 4 Justice from overtly misogynist groups like the Blackshirts in Australia, masked men in paramilitary uniforms who stalk the homes of women they feel have taken unfair advantage of the custody system. O’Connor realized early on that men marching in the street and shouting look like a public menace rather than like nurturing caretakers deserving of more time with their children. In England, the group has managed to offset that threat with goofy playfulness while holding on to enough dignity to maintain respectability. That balance might be even harder to strike in the States.

In the auditorium, Holstein’s fathers sat for half an hour and watched video footage of Fathers 4 Justice, much of it set to a stirring soundtrack of U2 songs. ”Would everyone who’s willing to be arrested please get on the bus?” Matt O’Connor called out during one protest. There were scenes of a father and his daughter playing with their pet sheep, which the father had dyed purple; scenes of dozens of men dressed as Father Christmas staging a sit-in at the children’s-affairs office of a government building; and scenes from two of the group’s largest protests: the Men in Black march (which featured about a thousand fathers, as well as supportive mothers and grandmothers, dressed in sunglasses and black suits, to symbolize their grief), and the Rising, a march through London that drew more than 2,000 protesters.

Afterward, Robert Chase, a 39-year-old clean-cut Dartmouth graduate who met with Jason Hatch and his colleague when they came to New York, led the group in brainstorming protest ideas of their own. Men started offering suggestions: they could protest from one of Boston’s duck boats; they could march to the harbor for a Boston Tea Party, only throwing their divorce decrees, not tea, into the water; they could dress up like Barney; they could dress up in burkas! The group seemed receptive to costumes, but there wasn’t much enthusiasm for storming court buildings.

”I’m not in the mood to get arrested,” one man called out. ”I got arrested enough during my divorce.” This got a laugh.

”I like the idea of a parade, but it needs to be funny,” another man said.

”Humor!” Holstein exclaimed. ”Humor works better than anger!”

For most of American legal history, the laws required judges to consider sex the most significant factor when making custody decisions, although which sex had the advantage changed over time. Until the mid-1800’s, under common law, a father’s right to custody in the event of a divorce was so strong that it practically functioned as a property right. Toward the end of that century, this principle was reversed by the ”tender years” doctrine — the presumption that young children need to be with their mothers — which lasted in a handful of jurisdictions into the early 80’s. For the most part, however, by the late 70’s, the ”tender years” doctrine had given way to the less prejudiced, but also less clear, directive that judges base their decisions on the so-called best interest of the child. Today many fathers’ rights advocates — particularly those who filed the 40-some class-action lawsuits demanding a 50-50 split of custody — would like to usher in a new paradigm: one that values parental rights as highly as the child’s best interest.

Michael Newdow is one of the fathers who have been trying to make that case. He is best known as the California emergency-room doctor who represented himself last year in a case before the Supreme Court, arguing that the words ”under God” in the Pledge of Allegiance violated the establishment clause of the United States Constitution. Newdow, an atheist, brought the suit on the grounds that the pledge forced the government’s spiritual views onto his daughter, impeding her freedom of religious choice. The Supreme Court ruled that Newdow, given the particulars of his case and his custody issues, didn’t have the standing to bring the suit. For five years leading up to his appearance before the Supreme Court, Newdow had two driving passions in his life: fighting for more custody of his daughter and fighting to eliminate ”under God” from the pledge. When the court dismissed his case, the two passions collided and combusted, the destruction of one cause taking the other down with it.

Though he still practices emergency-room medicine, Newdow finds time to tour the country, speaking at conferences and law schools about the separation of church and state. Last winter, I met up with him at the University of Michigan Law School just after he finished giving a talk to some students. He was carrying a guitar and looked a little flustered, two details that turned out to be related: during his talks, he likes to sing a song he wrote about the establishment clause, only this time he flubbed the lyrics.

Fast-talking and faster-thinking, Newdow, 51, is a tall, thin man who manages to look crisply dressed in even informal clothing.Conversationally, he toggles between two modes, aggrieved and outraged, and he has an expressive face that seems well designed to reflect those emotions. That evening, sitting in the lobby of the Michigan Union, he talked for close to two hours about his troubles — the custody battles he endured with his daughter’s mother (whom he never married); the impassioned exchanges that alienated the family-court judge; the injustices he feels he suffered at the hands of foolish mediators; the court appearances over all manner of arcane disputes, including whether he could take his daughter out hunting for frogs one night (no) and whether he could take her to hear him argue before the Supreme Court (again, no). Although the courts deprived him of final decision-making power over his daughter, who is now 10, he does spend about 30 percent of the time with her, a relatively generous arrangement. Nonetheless, Newdow, who has spent half a million dollars on legal fees, the lion’s share of those incurred by his child’s mother, claims that the family-court system has ruined his life. He’s a second-class parent, he said; he can’t do the things he’d like to do with his daughter. The system allows his daughter’s mother to stifle his freedom to care for his child the way he’d like. ”It’s as bad as slavery,” he said.

As a spokesman on behalf of fathers’ rights — or rather, as he makes a point of stressing, all parents’ and children’s rights — Newdow is a brilliant, confident speaker, but sometimes he lacks a light touch. Hyperrational, occasionally tone-deaf, he’ll admit that he knows enough to know that his logic often offends people, sane as it seems to him. Early on in our conversation, when he started to digress about the imbalance in reproductive rights — women can choose to end a pregnancy but men can’t — he cut himself off. ”That’s another issue, and it alienates people, and I don’t want to alienate you,” he said. ”Although I will eventually.” It wasn’t a threat, or a joke, or a regret — it was just, to him, by now, a probability.

The following day, Newdow delivered a second talk at Michigan, this time on the subject of family law, to 50 or 60 students who filled a classroom. (Newdow himself attended Michigan Law School before becoming a doctor.) While the students listened, tossing back free pizza that a student group had provided, Newdow began discussing Troxel v. Granville, a 2000 Supreme Court ruling that has been warmly embraced by fathers’ rights advocates. In that decision, the court held that a grandparent’s visitation rights could not be granted without a parent’s consent, even if a grandparent’s visits were in the best interest of the child. In Troxel, Newdow noted, the court stated that parental rights are ”perhaps the oldest of fundamental liberty interests recognized by this court.” If to be a parent is a fundamental constitutional right, he asked, how can the government violate that right without a showing a compelling state interest?

A hand went up. ”Isn’t the best interest of the child a compelling state interest?”

This is one of Newdow’s favorite questions. ”How do you prove what’s best for the child?” he asked. ”Somebody tell me what’s best for the child. Let’s take lunch. McDonald’s or make tuna fish at home — what’s best? O.K., lunch at home, you don’t risk a car accident, maybe the food’s healthier. McDonald’s, on the other hand, maybe it’s more fun, maybe the kid sees something new, gets the confidence to go down the slide for the first time. When you’re talking about two fit parents, who’s to say what’s best?”

But what also worried Newdow, he continued, was not the problem of how to determine what’s ”best” for the child, but rather the assumption that you can deprive someone of his or her fundamental parental right simply in order to make a child’s life more pleasant. Of course, he conceded, society has an obligation to protect those, like children, who cannot protect themselves. But there is a world of difference between protecting someone from harm and improving his life more generally. ”We’ve gone from protection to suddenly ‘make their lives better,”’ he said. ”And that’s a violation of equal protection — because you’re taking one person’s life and ruining it to make another person’s better. If you can show real harm to the child, the kind of harm that the state would protect any child in an intact family from — abuse, neglect — sure, of course, protect it. But when it’s just what someone thinks might be better for the child, you have to weigh that compared to the harm suffered by the parent.”

In short, forget for a moment about tending to a child’s optimal well-being: what about what’s fair? If a child’s parents are still married, courts don’t worry about whether it’s in the best interest of the child to go frogging late at night — so why should they have the power to weigh that issue the instant two parents separate? Split the custody 50-50, Newdow proposes, and let each parent make independent decisions during his or her time with that child.

A young woman with long dark hair raised her hand. ”So you want to just split the kid 50-50, like Solomon?” she asked. All around her, students looked either amused or incensed by the argument Newdow was making.

”Why is 70-30 so much better?” he countered. ”And if 50-50 is so terrible, why do courts have no problem with parents who mutually agree to 50-50 arrangements?”

A quiet girl in the front row had a trickier question. ”What about when one parent wants to do something that permanently prohibits the other parent’s freedom to exercise their own constitutional right to parent the way they see fit?” she asked, searching for an example. ”Say, getting her daughter’s ear pierced. You can do that on your own time, but it’s permanent.”

For that kind of thing, Newdow conceded, you go to court. Here his logic seemed to be leading him to strange places: a father could take his teenage son to a strip club, but over an ear-piercing, he’d have to go to court?

The young woman’s question illustrated the particular thorniness of parental rights. By exercising his or her own right, a parent may end up negating the other’s. An accuser’s right to hire an attorney doesn’t complicate the right of the accused to legal defense; my right to free speech doesn’t inhibit your right to the same. But if two parents are at odds, parental rights become a kind of zero-sum game of constitutional freedom.

David Meyer, a University of Illinois law professor who specializes in the intersection of family and constitutional laws, agrees with Newdow that the courts have recognized a fundamental parental right. The problem, Meyer says, is that so-called strict scrutiny — the process by which the court determines whether there’s a state interest so compelling that it should override a fundamental right — is complicated when multiple people in a single family are asserting their fundamental constitutional rights. In Troxel, he notes, ”the court was forced into a mushy kind of balancing test, balancing the interests of the children and the parents and all kinds of facts.” In his opinion in Troxel, Justice Clarence Thomas raised the question of why strict scrutiny wasn’t being applied. ”None of the other justices answered him,” Meyer told me. ”But implicitly the answer is: it just doesn’t work here.”

Although Newdow rarely loses his temper, his complicated rationales for simple solutions can exasperate those who engage him in any conversation about the subject of custody. Joining Newdow at an informal law-school dinner the night before he spoke, Christina Whitman, a former professor of Newdow’s, lost little time on congratulations before challenging him. ”Your [constitutional] right guarantees you equality in making your case before the judge,” she pointed out, ”but it doesn’t guarantee you equal custody. You have the right to an answer, not an answer you’d like.” Only if the court’s decision was arbitrary, she pointed out, would it be a violation of his constitutional right.

Newdow replied that the judges’ rulings are, in fact, arbitrary, often depending on the expert opinion of psychologists to whom he grants zero scientific credibility. He cited textbook cases of judges making absurd decisions based on their own value judgments about what kind of parent would be the better custodian.

”But just because unfair decisions happen doesn’t mean 50-50 is the answer,” she said. ”That’s a child’s approach to equality.”

The two went round and round until Whitman took a breather to ask how old Newdow’s daughter was. ”Ten,” he told her. Whitman laughed. ”Just wait two years,” she said, clearly speaking from experience. ”You won’t want her anymore.”

Standing on the plaza outside Boston City Hall, an observer had to take a close look, amid the sea of Red Sox caps, to see the signs of romance on Valentine’s Day. A teenager walked across the plaza with a handful of red and white carnations; a minute or two later, a man in a business suit passed by briskly, a Mylar balloon trailing behind him. As another man in a suit helped a young mother get her stroller down the plaza stairs, a deep chanting from the street below made its way to the plaza — the echoing, slightly eerie sound of shouted slogans magnified by a bullhorn: ”It’s Valentine’s Day, and we can’t see our kids!” And then: ”What do we want? Justice! When do we want it? Now!”

Robert Chase, the Dartmouth grad from the Fathers and Family meeting, didn’t have much luck persuading those fathers to take to the streets, but he had managed to round up 30 or so protesters, a few from New Hampshire, his home state, to march under the banner ”Fathers 4 Justice US.” (Similar protests were organized in 11 other cities across the country that day.) An entrepreneur who runs his own consulting business, Chase has custody of his two sons every other weekend. Several years ago, he lost the right to a third weekend per month when a judge determined that it was logistically onerous for the kids, which is what their mother argued in court. It was the last in a series of outcomes over the years that disappointed him. Chase, who speaks in considered, wholesome-sounding phrases, says that he has made peace with the arrangement now, especially since his children are teenagers with lives of their own. But he mourns the opportunities lost.

”We can’t reclaim the together-time we lost while they were growing up,” he told me. ”When you’re spending only two or four days a month with your kids, you can’t really teach them values, the difference between right and wrong. All you can do is love them, provide a positive example and hope they’re getting what they need when they’re outside your influence.”

In the years after the breakup of his marriage, Chase initially sought the help of various fathers’ groups, but he told me he felt that most of them ”didn’t do anything but sit around and complain.” Like Jason Hatch, he got interested in Fathers 4 Justice after reading about the group in the news. A father for the first time at 22, Chase, now 39, said it suddenly occurred to him that his older son, now 17, could be a father himself in five or six years. He decided he should take whatever action was possible to make sure his sons and any future grandsons wouldn’t encounter the same custody system he faced, should they ever suffer an unhappy divorce.

Outside City Hall, Chase and his team, mostly men but including a few women, started shuffling their way down Congress Street, some of them blowing whistles and horns. One man wore a devil’s mask, with horns atop his head, and a judge’s robe; another man in a judge’s robe looked even scarier, with a mask of blue eyeballs, no nose, missing teeth, a misshapen skull and several well-placed boils. Other men, including Chase, were dressed in sunglasses and white decontamination suits that had purple hand prints (a Fathers 4 Justice symbol) smeared on them. Something about the mix of white and the flowing robes lent the men a vaguely Klannish aesthetic. As they whistled and bellowed their way down the street, they seemed to have lost sight of Ned Holstein’s exhortation to try humor, not anger. A mother with her child approaching them on the street crossed over to the other side.

After a half-hour or so of chanting and marching, the group arrived at the main family-court building in Boston. At the plaza of the courthouse, one protester started beating a drum. A compact man with a neatly trimmed beard, a green tie and a houndstooth cap left the courthouse and passed the protesters. ”It could happen to you!” the protesters chanted.

”It did happen to me,” the man said. ”She went nuclear on me.” In the fathers’ rights community, the real weapons of mass destruction are false allegations of abuse. Fathers’ rights advocates claim it’s all too easy for women to use that strategy; feminists counter that too many family-court judges dismiss women’s valid concerns about domestic violence. ”Two years and three-quarters of a million dollars later,” the man continued, ”I got full custody of my kids, and was fully exonerated. But I’ve been living this for two years.” Now the man, who declined to give his name, watched as some of the protesters performed some street theater: a monster in a judge’s robe tearing up a kid’s photo, one of the fathers punching him to the ground, a man in a decontamination suit with a broom pushing at the heap of a human on the street. ”I don’t know about this,” he said, gesturing at the protesters’ garish pantomime. ”But the system does need fixing.”

While they were marching, members of Chase’s group passed out fliers promoting fathers-4-justice.org and detailing all the harms that children without fathers are more likely to suffer — drug problems, depression, less education. Unlike Michael Newdow, Chase pays little attention to legal rights, arguing exclusively that the interests of the father are aligned with those of the child, given all the social-science research that suggests that fatherless children fare poorly.

But some scholars argue that this reasoning mistakenly assumes that children’s welfare works roughly on a sliding scale — that if children with no fathers at all suffer various emotional and social setbacks, then children who see their fathers only, say, every other week might suffer roughly half those setbacks. Margaret Brinig, a professor of family law at the University of Iowa, has examined a longitudinal study of a national sample of more than 20,000 junior-high and high-school children, close to 3,000 of whom had divorced parents and lived with their mothers. Studying that select sample, she found that there was only one sort of custody arrangement that noticeably harmed children: having the child visit the father for sleepover visits only several times a year. Children in such arrangements, Brinig found, were significantly more likely to suffer from depression and fear of dying young. But whether a child had a sleepover with his father a few times a month or a few times a week didn’t seem to influence that child’s well-being in any measurable way. (Kids who had sleepovers with their fathers several times a month were less likely to abuse drugs and alcohol than kids who didn’t, but Brinig posits that result as an exception to her overall conclusion.)

Fathers’ advocates like Ned Holstein argue that Brinig’s study might have found more positive results if more of the fathers in it had 50-50 custody, creating more intimate relationships, rather than measuring the difference between, say, one night a month and two nights a month. ”It’s like prescribing one aspirin for cancer or two aspirin,” he said. But Brinig remains wary of a presumption of joint physical custody. ”There’s quite a bit of evidence to suggest that joint physical custody is definitely not good for kids when there’s a high-conflict situation between the parents,” she told me. The more shared the custody, the argument goes, the more the parents have to interact and the more the children are exposed to nasty exchanges and power plays. Fathers’ rights advocates, by contrast, contend that it’s the current winner-take-all system that creates conflict by forcing fearful parents into vitriolic attacks.

Since the early 90’s, scores of studies on the subject of joint custody have been fired back and forth between the competing camps — studies suggesting that joint physical or even joint legal custody, which gives each parent some decision-making power, fuels conflict; studies claiming that sons fare worse with a mother’s sole custody; studies suggesting that children crave stability; studies suggesting that joint physical custody improves child-support payments; and so on. Some of the studies, accurate though they may be, can lead to difficult, even distasteful conclusions. Should policy really be based on studies that basically conclude it doesn’t matter how often a father sees his kid, so long as it’s more than a few times a year? On the other hand, it’s almost impossible to measure how a presumption of joint physical custody affects the motivations of parents on both sides, how that extra bargaining chip might be abused. In one particularly influential study, researchers at Harvard and Stanford found that even in cases in which joint physical custody was granted, the arrangement often devolved into a primary-custodian situation, with the mother taking more responsibility — but perhaps receiving less child support under the equal arrangement.

Robert Mnookin, director of the Harvard Negotiation Research Project and a professor at Harvard Law School, is the rare expert who concedes that each side has legitimate concerns. A presumption of joint physical custody would have ”some nice symbolic attributes,” he told me; but he worries about how it would play out in practice. He notes that the parents whose custody negotiations end up going all the way to court tend to be the parents who fight the most. In those cases, he argues, forcing judges to implement joint physical custody is a bad idea for the kids, since it only perpetuates their exposure to the conflict. He contends, however, that if divorced parents know that a judge is disinclined to award joint physical custody in circumstances with a high degree of conflict, it creates an incentive for a parent who wants sole custody to create conflict. Mnookin says he doesn’t favor the presumption of joint physical custody, although he concedes that without one, the system gives mothers an advantage. ”In times of cultural transition like this,” he said, ”the law struggles.”

As Chase’s group was marching through Boston, men all over the city paused to nod grimly and unload stories of how they felt they’d been abused by the custody system, or of how a friend had been. They weren’t offering broad theories about constitutional rights or citing chapter and verse from social-science studies. Their complaints were mostly about the logistics of the system, its (to them) arbitrary rule over their finances, its judgments about their life choices, the punishments it doles out, its power to splinter into useless small pieces whatever relationship they’d struggled to build with their children — all complaints that probably would have been echoed by as many women, had it been women marching down the street protesting about mothers’ rights to custody.

One man in a blue oxford shirt ran down from his third-story office to get some contact information from Chase’s group — his brother-in-law, he said, was about to be arrested because he could no longer keep up with the child-support payments the court demanded. Another man said he had lost custody because he was home with the kids. ”And a man who’s home with the kids isn’t a homemaker; he’s just unemployed,” he said. Another passer-by had lost custody of his kids, he said, because he wasn’t the primary caretaker; the child-support payments were killing him, he said (in Massachusetts, they can run up to 30 percent or more of gross income) and even still, he didn’t have nearly as much time with his kids as he would have liked. The court held his wife in contempt for blocking his visitation, ”but she didn’t care,” he said. ”It’s a slap on the wrist.” A man with a Scandinavian accent, wearing a black zip-down sweater, said that he was supposed to see his kids every third weekend but that his wife moved out of state and uses every legal loophole she can to stop him from seeing them.

Boston that morning felt like a city of walking wounded — men who stopped on their way to or from their workplaces to compare notes with one another about their losses; men who seemed eager to get someone to pay attention to what they saw as the tragic absurdities of their lives. Their stories came out fragmented, no doubt one-sided, but moving nonetheless. They were short chapters in much longer novels that could be written, that have all but been written, in fact, by those who have best captured modern-day male alienation — Andre Dubus, Robert Stone, Richard Ford, David Gates — with their stories of imperfect men and frustrated women and misunderstandings and low expectations all around. The city blocks that Chase’s protesters walked must have contained thousands of divided families, and every one of the fathers in those families has hundreds of stories, every one of which he would happily tell to a family court, if only the judge had the time to really listen.

The morning Jason Hatch was scheduled to scale the building on Downing Street, Matt O’Connor, the Fathers 4 Justice founder, was sitting nervously at the coffee shop of the Thistle Hotel in London, a few blocks from Downing, waiting for a phone call. Leaders of social movements may have once hailed from the ranks of unions, sweatshops and churches, but it seems inevitable that in today’s culture, O’Connor, one of England’s most successful activists, had a career as a brand designer for hip restaurants. Sitting with his girlfriend at the time, Giselle, a yoga instructor, O’Connor left his cellphone out on the table, waiting for it to sound its customary ring: the theme song from ”Mission: Impossible.” In the days before, whenever he spoke to me about Hatch’s plan, he would take the battery out of his phone to thwart the government agents he was convinced could otherwise listen in. The police, he suspected, had been given advance warning of a few recent Fathers 4 Justice stunts they had managed to disrupt. As he waited for the phone call, he rehearsed for me some of his sound bites: ”Our government is turning a nation of fathers into a nation of McDads” was one; ”We have a government of dysfunctional misfits who are trying to create a generation of dysfunctional kids” was another.

O’Connor wasn’t sure he’d have the chance to use his one-liners. Fathers 4 Justice had had a string of bad luck lately, and the security at Downing Street was thick. He was in the process of describing to me how Hatch had cased the building when his phone rang. It was a colleague on the scene at Downing Street calling from his cellphone. ”He’s up!” he yelled. O’Connor, in his camel’s-hair coat and snakeskin boots, and his girlfriend, chic in oversize sunglasses and a broad hat, ran out the door of the coffee shop and hailed a cab. Heading for the site a few blocks away, catching their breath in the taxi, they could hear the sirens of police cars heading in the same direction.

When we arrived at Downing Street, the area surrounding the building had been cordoned off. High up enough that he looked quite small, Hatch, dressed as Batman, was standing on a ledge, along with two other men, both Fathers 4 Justice members, one dressed like Robin, the other dressed like Captain America. The three men had driven a truck up to the side of building and onto the pavement, mounted a ladder and, without a hitch, climbed up. They had made their way across the balcony to the corner of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office building, where they stood on what looked like a fairly narrow perch. They hung a large banner, reading ”Access Denied.” The police apparently didn’t notice anything until the men were already up and a crowd of onlookers had started cheering.

A cluster of boys in their school blazers waved wildly up to the men. Hatch put on his mask and twirled his cape. Six or seven teenage girls, also waving wildly, started screaming, Beatles-fan style, and blowing Hatch kisses. He blew a few back. Some more tourists and locals joined the crowd, and several large men in sunglasses and street clothes seemed to be keeping a particularly keen eye on the crowd. ”How are you, darling?” Giselle said into O’Connor’s cellphone, looking up nervously at Hatch, who had his own phone pressed to his ear.

Reporters lined up to get their sound bites from O’Connor. The press turnout was solid but perhaps a bit perfunctory. The media in England had already addressed the security angle in previous coverage, and after Buckingham Palace, every possible angle on paternity in Britain had been thoroughly worked. ”Right, we don’t need to hear their message again, do we?” I overheard a BBC reporter say into his cellphoneto his producer. The press had also already exhausted its love affair with Hatch as Hero Dad. It had become public knowledge that Hatch had been convicted of threatening his second wife and that he had another child, with his first wife. After he scaled Buckingham Palace, his girlfriend told the press that she had dumped him because he was devoting too much time to Fathers 4 Justice and not enough to their baby. (The two have since reconciled — ”I was very post-partum” at the time, she told me — but that story hasn’t received as much play.)

As the afternoon wore on, the already gray day turned a little grayer, and a cold, wet wind picked up. The reporters down below, in scarves and boots, complained about their chilled feet. Several hundred feet up, on the ledge, it could only have been colder and windier, with superhero tights providing little protection. The three men had brought a knapsack filled with chocolates and Red Bull, but eventually the cold and the fatigue got to Captain America, who came down around 5 p.m. An hour or two later, Robin capitulated, too. By then, the crowd of bystanders had pretty much dissipated, but Hatch stayed put, his cape wrapped around him for warmth. Long after everyone else had gone home to dinner and kids and, finally, bed, he was still on the ledge, an outraged father, determined, cold and alone.